Wyatt Earp is not a good movie. Too much of the first hour involves a fortyish Kevin Costner playing a callow youth. The next two hours are equally flat, full of loveless romance, joyless friendships, and dull violence.

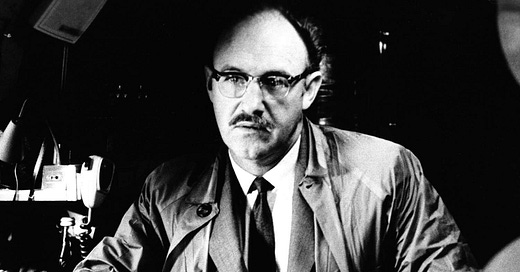

But an hour in, there’s one good scene, and of course it belongs to Gene Hackman.

Hackman plays Wyatt’s father, a judge. Wyatt has stolen a horse and been caught. It’s an offense punishable by death. Hackman appears at the jail during a thunderstorm, like some old testament patriarch, to bail out his son.

I gave him five hundred dollar bail and told him I’d defend you at your trial. There’s not gonna be any trial. Because if they try you, they’ll hang you, and if they catch you, they’ll hang you. So you get on that horse, Wyatt, and you ride. Keep riding, till you get out of Arkansas. And you don’t come back here ever.

It’s a terrific scene of a disappointed father expressing love through banishment, and a judge who believes in the law having to break it to save his son’s life.

Like Robert Duvall, Hackman could leaven a bad film with one good scene, or make a good film better. He could play a villain, a loser, a bigot, or a clean-cut hero—and do it all startlingly, originally.

How many gruff coaches have you seen melt and show hearts of gold to their players? In Hoosiers, Hackman plays a coach whose big heartwarming moment is deciding not to play a kid whose stitches have opened up. This is not a warm and fuzzy guy, but a man willing to maim children in service of victory—a fact he’s learned about himself, detests, and is struggling to overcome.

Unforgiven is close to a perfect western. What so unnerves about Hackman’s performance as Little Bill Daggett is how right he is, how justifiable within the parameters of his job. He errs on the side of mercy by fining the two cowboys who knifed a prostitute instead of whipping them.

Haven't you seen enough blood for one night? Hell, Alice, it's not like they was tramps, or loafers, or bad men. Just two hard-working boys that was foolish. If they was given over to wickedness in a regular way...

Of course, we the audience haven’t seen enough blood, either. The bad guy of the film is the one keeping us from the kind of Old West shootout we want. His decision is disgusting and unfair—but in a peacekeeping sense, not entirely unjust.

Later, Little Bill beats, arrests, and humiliates the assassin English Bob. Before running him out of town, he says:

I suppose you know, Bob, if I ever see you again I'm just going to start shooting and figure it was self-defence.

Hackman delivers the line as less of a threat than a veteran lawman’s resigned caution to a fool who might do it anyway. Incrementally Little Bill creeps toward fascism, whipping Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) in both an ugly and no doubt deliberately racially charged scene.

Now Ned, them whores are going to tell different lies than you. And when their lies ain't the same as your lies... Well, I ain't gonna hurt no woman. But I'm gonna hurt you. And not gentle like before... but bad.

You can read Little Bill as a black hat villain from the jump, a corrupt and mysogynist sheriff who deserves to be gunned down. The film allows that reading. But it’s more nuanced and I think more accurate to see him as carried away by violence. Every beating is administered in the belief, honest or not, that it will curtail worse and further violence. Not gentle like before…but bad. The repulsive attraction of blood is as much a part of him as Eastwood’s Will Munny. Little Bill dies like a tragic hero having brought about his own death. His moment of anagnorisis, of nihilistic understanding, is given in Eastwood’s perfectly delivered eulogy:

Deserve’s got nothing to do with it.

Hackman did so many great films—and was great in average ones, and good in bad ones. Quick and the Dead, Royal Tenenbaums, The Birdcage, Young Frankenstein, French Connection, Crimson Tide, the Poseidon Adventure. I don’t know if David Mamet’s Heist holds up, but two hours of Hackman and Ricky Jay uttering dialog like “Don’t you want to hear my last words?” “I just did.” is something I’m glad exists. Same with Absolute Power, a political thriller where in the opening scene, Hackman goes from a philandering louche to a brutal psychopath to a coward in about ten seconds. The scenes of him recovering from addiction in French Connection II are great as well, and that film is much better than it has any right to be.

The Conversation and Night Moves are special to me. Harry Caul and Harry Moseby are losers, loners, but also prideful small businessmen, craftspeople in a world of bullshit and bullshitters. They informed my sense of the private eye story. Hackman’s sad last days call to mind the endings of both films. Characters so lost they may as well never have been found. Horrifying, but not surprising given the squalid state of things.

Gene Hackman was both an artist and a professional, sometimes leaning more toward one or the other. I haven’t read his novels, but it’s fitting he ended his days writing genre fiction, as it’s also a mix of art and craft. We didn’t deserve him and there won’t be another like him.

The book launch for The Last Exile is Wednesday, March 12, starting at 6:30, at the Irish Heather in Vancouver. Book sales, food, drinks… And on March 26th I’m in conversation with Charles Demers at the VPL Central Branch. Its official release date is March 25th, but it’s already on the local bestseller list. Out in the US in October.

Great point about being able to elevate some seriously lacking works. The Firm is, by most standards, a crummy-to-mediocre movie. But Hackman's Avery Tollar shines in every scene he's in, making his subplot fairly memorable in a mostly forgettable movie.

Hackman was a crazy good anti-hero. That's hard to pull off even once in a career, and he did it multiple times.

Great post, Sam. The Conversation is a masterpiece. So is Unforgiven.