The Last Exile is available for pre-order now!

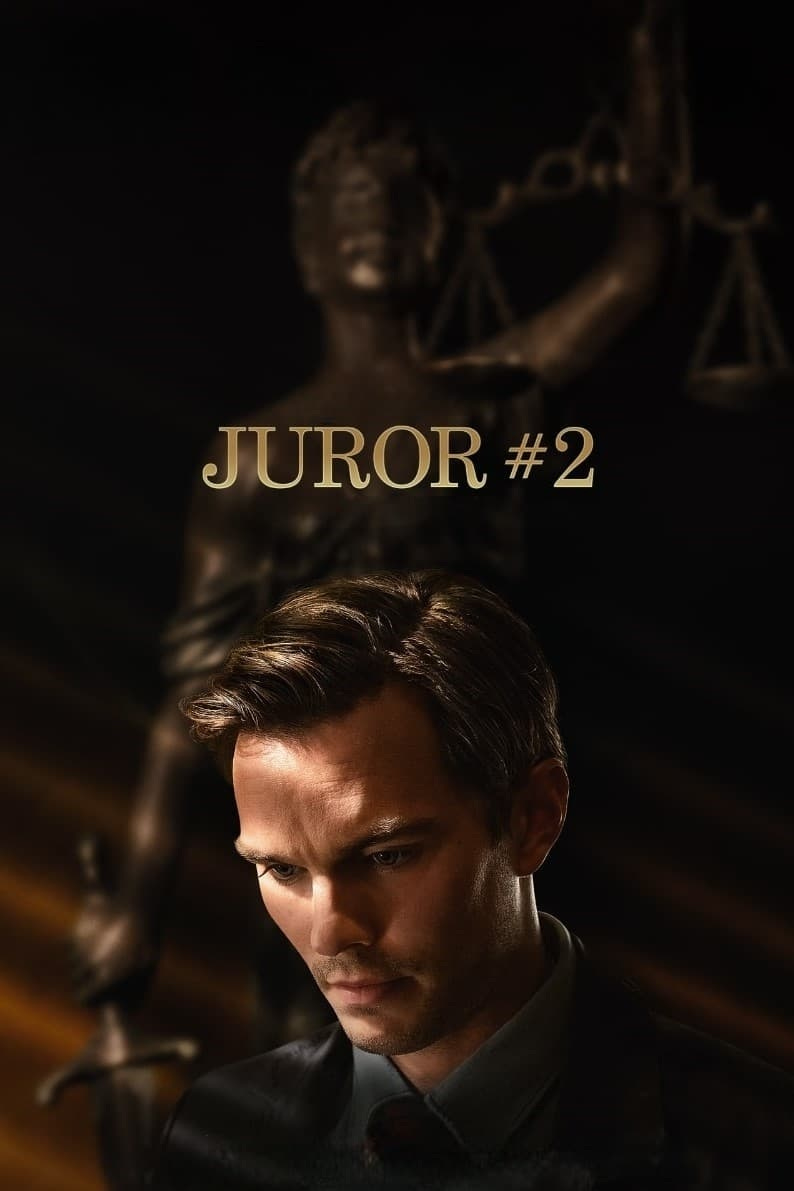

Clint Eastwood’s Juror No. 2 shares some DNA with 12 Angry Men, yet it has more in common with Mystic River, a film about the moral compromises that spin out from a murder than the investigation itself.

At heart, Clint Eastwood is a New Hollywood filmmaker with studio work habits. That 60s and 70s generation of stars and directors worked within the studio system, yet when they could, chose projects that pushed the boundaries of moral complexity. Eastwood films tend to focus on flawed and sometimes deeply fucked up characters. Instead of judging or punishing them, his films simply sit with their complexities, sometimes to our discomfort.

One of my favorite Clint anecdotes is how he rewrote the script for Unforgiven, then looked at the changes he’d made, realized his version was worse than David Webb Peoples’ brilliant script, and went back to the original. Eastwood is not an auteurist. He treats filmmaking the way a studio director does—find a great script and film it and try not to fuck it up.

There’s a moment in the Eastwood-produced documentary Straight No Chaser which shows Thelonious Monk in the recording studio. He lays down a take, after which the recording engineers tell Monk they missed what he recorded. In Monk’s world, and I think Eastwood’s, an artist lays down the best version they can and then moves on. How much better is a Gene Hackman (or Toni Colette) performance going to be on the thirtieth take?

Juror No. 2 begins starts with the jury being told their best qualification to serve is their reluctance. It's because they don’t want the power to determine defendant James Sythe’s fate that they can be trusted with that job. In most cases, that sentiment would be true.

One of the jurors (Nicholas Hoult), knows more about the case than even he realizes at first. As the knowledge dawns on him that Sythe didn’t do it, he realizes that coming forward would jeopardize his own life. He has a baby on the way, all the other jurors think Sythe is guilty, and the DA (Toni Colette) is pinning her re-election to a guilty verdict. Exactly how much is the truth and justice worth when no one wants to work for them?

Conclave came out the same week as Juror No. 2. It’s also a jury movie of sorts, about the closed door politicking around the selection of a new pope. Without spoiling anything, Conclave takes the idea to a novel but recognizably satisfying conclusion.

And Juror No. 2 doesn’t.

To me that’s what so many of Clint’s movies do so well—resolve without really resolving anything. I don’t mean they’re unfinished or undercooked, but they don’t pass judgment on the characters. Their rightness is left to us to determine, and he doesn’t tilt the scales either way.

In a year of films that seem evenly split between derivative junk and wildly ambitious but flawed directorial dream projects, Juror No 2 doesn’t fit really fit anywhere. Yet it’s a great film, in part because it’s not trying to be anything other than a great story. And great stories are more troubling than we want them to be, because they’re about ourselves.

Note: the film didn’t play anywhere close to Vancouver, so Carly and I drove two and a half hours down to Bellevue, a charmless corporate exurb of Seattle (where Left Coast Crime was held earlier this year). On the way back, the border guard asked what our business was. When I said “We drove down to see a movie,” he seemed confused. “You drove all the way down there to see a movie?”

It was a very good movie.

My favourite Eastwood anecdote is Sergio Leone's comment on casting him, that he loved Eastwood because he had only expressions: one with the hat, and one without.

It says a lot about the sorry state of cinema that a Clint Eastwood movie would only play as a limited release before streaming... I'm old enough to know we are missing something we all our personal screens. I salute you, Sam, for driving to see it. I haven't found a theatre near me. Looking forward to this one.