Writing advice has become an expected part of marketing and literary citizenship, which means there’s a lot of it of dubious value. Feel free to ignore all of this, or trust but verify. In any case I don’t think it’ll hurt.

What follows are five rules in no particular order, distilled from reading reams of bad and good writing. The three pet peeves are admittedly subjective, but are included because I really dislike them.

1. Care on the sentence level.

Almost every other flaw can be forgiven if a writer cares about language and takes the time to make their sentences lively and rich and idiosyncratic.

It’s a strange truism that the most bombastic marketers of their own writing, the people with pay-to-pay platforms and email handles like JohnSmithAuthor@ReallyRealWriter.com, compose blah sentences like:

“She walked across the room and crossed into the kitchen. Bob stood there opening a beer. He looked mad enough to burst, and she knew he was so angry he could explode at any minute.”

Cliches, repetitions, clanky construction—even if you care about style, you’ll end up doing this some of the time. Try not to do it all the time.

2. Here’s an Idea, Have a Point

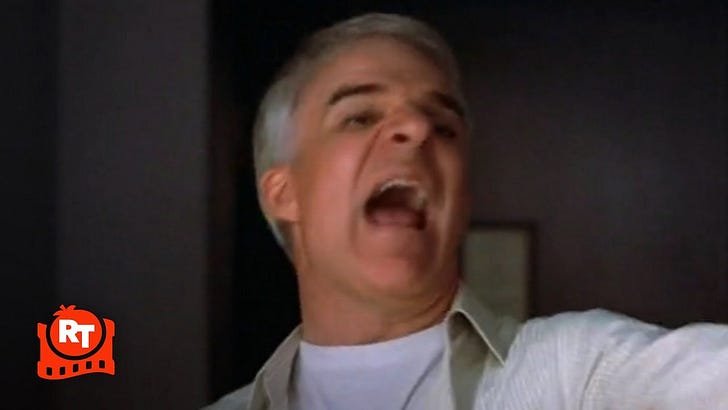

“I mean, didn't you notice on the plane when you started talking, eventually I started reading the vomit bag? Didn't that give you some sort of clue, like hey, maybe this guy is not enjoying it? You know, everything is not an anecdote. You have to discriminate. You choose things that are funny or mildly amusing or interesting…And by the way, when you're telling these little stories, here's a good idea. Have a point. It makes it so much more interesting for the listener!”

I can’t say it any better than Steve Martin.

3. Make every scene dramatic

David Mamet’s all-caps memo to the writers room on The Unit is a pithy read about drama.

EVERY SCENE MUST BE DRAMATIC. THAT MEANS: THE MAIN CHARACTER MUST HAVE A SIMPLE, STRAIGHTFORWARD, PRESSING NEED WHICH IMPELS HIM OR HER TO SHOW UP IN THE SCENE…

ANY SCENE, THUS, WHICH DOES NOT BOTH ADVANCE THE PLOT, AND STANDALONE (THAT IS, DRAMATICALLY, BY ITSELF, ON ITS OWN MERITS) IS EITHER SUPERFLUOUS, OR INCORRECTLY WRITTEN.

Exposition, backstory, a character unburdening their feelings—it’s not that you have to get rid of this stuff, but you have to make it dramatic. To mobilize it in order to move the story. Why is this character telling this anecdote? What does she want to get out of it? What are the stakes? Those are dramatically critical questions.

4. Details that Suggest

Chandler described a character as having “a face like a bucket of mud.” It’s a great simile that conjures to mind not just an appearance but a life story.

You can’t describe everything, so find the details that suggest the rest. Imagist poets like H.D. and Marianne Moore excelled at this (we’re in such a bad state culturally that suggesting someone read poems is both rare for the reader and self-consciously awkward for the suggester).

The right details also tell us about the person observing them. This is from Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel:

Blood from the gash on his head— which was his father’s first effort— is trickling across his face. Add to this, his left eye is blinded; but if he squints sideways, with his right eye he can see that the stitching of his father’s boot is unraveling. The twine has sprung clear of the leather, and a hard knot in it has caught his eyebrow and opened another cut.

5. ‘I’ll Fix It Later’

I’ve heard multiple aspiring writers voice a sentiment like this:

Thanks for the notes on my work! Instead of implementing them, I am going to submit this to publishers right now. I’ve put a lot of time in already, but if someone is interested, I’ll be happy to revise it again for publication.

Why is this bad? First, how much time you’ve put into a story, how many revisions, etc., is irrelevant. An editor or agent is only going to read it once. They will judge the story, and you, on what they have before them.

Second, the writer is putting off the hard work—not just of implementing the notes, but thinking about which notes to implement. When you get feedback, you shouldn’t agree with all of it. You also shouldn’t argue with it. They’ve given you an opinion of what they think works, but it’s still your call.

It’s not up to anybody else to make your story good.

3 Pet Peeves

1. The Cool Tough Guy Who’s Also Me

“You’re going down,” the big man snarled.

Tree Parkman didn’t flinch. Instead he just waited for the big man to swing then caught him in the chest with one uppercut then another and then a third. Wham! The big man went down.

“Anyone else?” he said, peeling his eyes around the bar.

There were no takers. He uncapped a Rolling Rock, his drink of choice, and placed a quarter on the bar for a tip. The beautiful waitress smiled at him gratefully. Def Leppard began to play as he walked out.

You get the idea.

2. ‘It’s Really about Trauma and Fatigue’

A few years ago, the dead wife or daughter was reviled as an embarrassing (and misogynist) device designed for unearned sympathy. Now, every horror movie, every character on a streaming service drama, and seemingly every writer, is frolicking in the land of You Just Don’t Understand My Grief.

I don’t want to understand your grief. I have my own, thanks.

A scene or chapter or episode that flashes back so we really, like, understand what the character has lost is unnecessary, undramatic, a waste of time.

3. ‘No, See, This is Just Book One’

The Marvel Universe was built on the characters and stories of a legion of great artists, from Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko to Ed Brubaker and G. Willow Wilson, who often didn’t get the royalties or credit they deserved. Don’t confuse ownership of IP for storytelling intent.

A lot of aspiring writers want to create a universe or a multi-book saga. Great. But start with one story that stands on its own. Don’t leave things to be explained or developed later. Throw out anything not necessary to this particular story. If a character is kinda dull for the first book but really develops in the second, skip the first.

That’s all of them. As I mentioned before, bad writing happens even if you care. Just try to make it happen as little as possible. Being professional, reading a lot, and sympathizing with your reader are the best habits to cultivate.

Montecristo commissioned a literary short story from me, “Fancy Seeing You Here,” which is now up on their website.

Speaking of short stories, Mickey Finn 5 is available now from Down and Out Books. Michael Bracken’s hardboiled/noir anthology series is great.

The Last Exile will come out next spring, but can be pre-ordered ahead of time, please and thanks!

Beautiful, Sam, and for all my Del Griffith stans: “You wanna hurt me? Go right ahead if it makes you feel any better. I’m an easy target. Yeah, you’re right: I talk too much. I also listen too much. I could be a cold-hearted cynic like you, but I don’t like to hurt people’s feelings.”

Great stuff, Sam. I’ve been a full-time editor for fifteen years now and have encountered all of these.

No. 1: This reminds me of the many times I’ve run into what I call “stage management sentences”: “Jack crossed from the left side to the opposite corner and aimed a slashing kick at Marco, who dodged to the far wall and spun a half-turn on one foot as he reached carefully with his right hand for the knife tucked into the back of his belt with a blood-flecked grin.”

Not only is this tedious, but it denies the reader their right — and want — to see the action in their minds the way they might choose to see it. That distances the reader from the page. It’s like telling the reader: “I’m not just writing, I’m doing the reading for you.”

How about “Jack’s kick met empty air, and Marco reached for his knife with a grin.”

No. 2: I see this a lot in the writing of those clearly in thrall to Elmore Leonard and his jivey, louche, loose-limbed dialogue. Somehow these writers miss that a) these seemingly lazy exchanges never go on for long; b) his characters almost never speak at monologue length; and c) every sentence of these exchanges does the crucial and economical double duty of advancing the plot and developing something new about the characters that’s as pertinent as it is interesting. It’s nowhere as easy as it looks.

No. 3: Usually this lack of drama turns up when the writer insists that they have to explain the story before telling the story. And this usually happens because the story starts in the wrong place. A typical tell:

“I awoke to see a sheriff’s car pulling into the driveway, and reached for my husband. Only he wasn’t there.

“Steve and I were married six years ago after a whirlwind weekend in Vegas. He never talked much about his past ….” (Continues for two pages)

No. 4: Part of the problem here is that Lee Child has spent years telling writers that there’s nothing “wrong” with telling with flat character description. From The Big Thrill: “He said writers are called ‘storytellers, after all, not story showers.’ Because of the show-don’t-tell rule, Child thinks that many writers are so scared of ‘telling’ that they manipulate their work, such as having characters peer in a mirror and describe themselves, rating their own looks. ‘Who does that in real life?’ Child laughed. ‘There’s nothing wrong with just writing ‘he was a tall man with brown hair.’” And the unspoken mic-drop here is: “Do we think we know better than Lee Child?”

I’d respond with: “Do you want your books to be read more than once? To reveal deeper layers and new pleasures with each subsequent reading? To he admired and discussed years from now?” Of course you do. I know few authors cynical enough to say: “I want to write a book you’ll furiously flip pages through to find out who did what to who on a cross-country flight before leaving the book in the seat pocket, forgotten by the time you gather your bags.”

No. 5: One thing I rarely see discussed in conversations about storycraft is the art of finding the perfect balance between how much to reveal n and how much to show, especially in the service of a series. I’ve worked with authors who err on the side of too much withholding, confusing suspense with confusion. Or perhaps apathy. Years ago, I watched the TV series BURN NOTICE, and found it good fun until I picked up on the weak execution of its structure: there’s an episodic story arc, with a season arc and a series arc nested within. Too often each episode made an apathetic nod toward the bigger arcs (“Fiona, that guy you let into my warehouse — what did he look like? And did you look inside that envelope and see those compromising pictures of me in Kinshasa from ten years ago?”) while doubling down on the episode arc. Too much withholding for me; I felt manipulated and I soon gave up.

As for your pet peeves:

No. 1: I come across several fantasy-projection stories a year — usually the male equivalent of Mary Sues. And I usually find in interviews with these authors that they were raised on a steady diet of Travis McGee and Spenser and Amos Walker and the like — knight-errants who kick ass (especially after being shot in the shoulder), always get the girl, speak truth to power, and, before they turned thirty, were boxers and stevedores and government operatives and baseball players and gourmet chefs. They’re so ridiculously front-loaded that they transcend realism, thus making it all but impossible (for me, anyway) to maintain the fictive dream. Usually the authors of these stories throw in a few tiny flaws in an unconvincing effort to keep them in human scale, but even those seem calculated to generate sympathy (the occasional beating, the cheating girlfriend). Your imagined scene is a perfect representation of this type.

No. 2: One thing I see a lot is what I call Unearned Sympathy Syndrome. In these stories, the protagonist suffered a tragic loss in their formative years, off the page or in flashback, and thus the character’s anger and alienation manifests itself in weapons-grade rudeness or inarticulate mopiness that bends everybody to their will because, dammit, YOU CAN’T UNDERSTAND HOW MUCH I’VE SUFFERED, DAMMIT! I OCCUPY THE MORAL HIGH GROUND AT ALL TIMES NO MATTER HOW SHITTY I AM TO EVERYBODY IN MY ORBIT! It’s an assigned dynamic from the start, and rarely one that’s earned in the present-day story.

No. 3: Pretty much the same as my note on No. 5 above. The more you withhold from the reader, the more they’ll withhold their time and money from you.