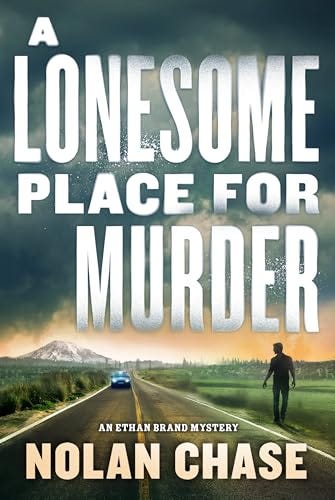

Publishers Weekly interviewed Nolan Chase ahead of the release of A Lonesome Place for Murder, the second Ethan Brand novel. We talked 70s movies, pen names, the Pacific Northwest, and the great Josephine Tey.

You can pre-order A Lonesome Place for Murder from Bookshop.Org (US)

Or pre-order from Indie Bookstores (CA)

Or from Barnes and Noble

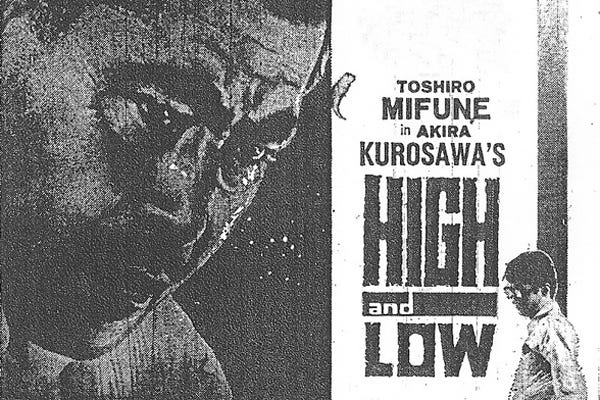

The first hour of High and Low is a relatively faithful adaptation of King’s Ransom, transported to midcentury Japan. Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an executive trying to modernize the National Shoe factory without compromising quality. After he mortgages everything he owns to buy a controlling share of stock, he learns his chauffeur’s son has been kidnapped.

This moral dilemma sits at the heart of the film. Do you sacrifice your future and everything you’ve worked for to save the life of a child? Gondo hesitates. Why him and not someone truly rich? (Because the kidnapper says so.) Will the police catch the kidnapper and retrieve his money? (Maybe.) Is there any guarantee that even if hands over the cash, the child isn’t already dead? (None whatsoever.) This has the feel of a Biblical test, with Gondo as Job or Abraham.

(mild spoilers ahead)

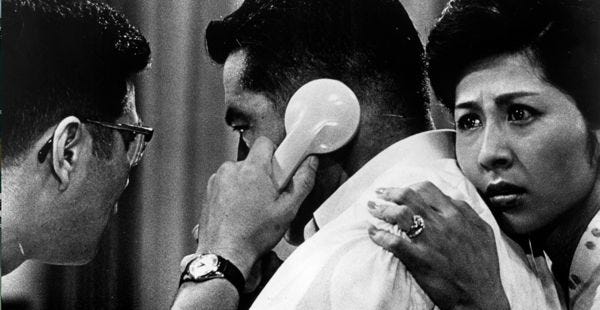

Gondo’s decision is different than the one made by Douglas King in King’s Ransom. Where King decides ultimately not to pay the ransom, Gondo does. In a terrific film sequence, he boards a train with the money placed in slim leather binders—slim enough, he realizes, to fit through the windows of the train. The child is returned safe, and the lead detective (Tatsuya Nakadai) and cohort do their best to catch the kidnapper and return Gondo’s money.

In the last hour and a half, the film diverges from the novel. Gondo suffers the fate he expected. The press coverage of his sacrifice has earned him national sympathy, but he can’t pay his bills with national sympathy. He loses his fortune, his house, and finally his job.

The second half contains artsy flourishes, most notably the burst of red smoke in an otherwise black and white film, signifying that the criminal has burned the binders that contained the money.

Yet the second half is also more of a procedural, even than the novel. The cops chase down leads, many of which tell them something about the kidnapper but not enough. They replay the ransom phone call, pinpointing the background noises. They have the chauffeur’s child draw the view from the hideout, attempting to match this to the scenery. They talk to Gondo’s coworkers—“what a bunch of assholes,” one of the cops says of the shoe executives.

In his letterboxd review, Chapo Trap House’s Will Menaker calls High and Low “part of a lineage of painstaking procedurals about the investigation of a crime that become a forensic examination of the society in which they occur. It goes M--->High and Low--->The Boston Strangler--->Memories of Murder—>Zodiac.” (To which I’d add Madigan, Naked City, He Walked By Night and All the President’s Men).

(larger spoilers)

If the film has a flaw, it’s the last half hour, where the kidnapper’s identity is revealed. He’s killed his accomplices, and Nakadai wants to nail him for the murders, not the kidnapping, ensuring he’ll get the death penalty. It drags the film out unnecessarily, and involves a slightly strained plot to force the killer to re-enact the crime.

But the film ends strong, with a chillingly ambiguous confrontation between Gondo and the kidnapper. Why him? Gondo asks. The kidnapper explains that he grew up poor, looking up every day at Gondo’s house on a hill. Is this a reason, an excuse, or bullshit? Any and all.

In his Hollywood memoir Everywhere an Oink Oink, David Mamet mentions an unproduced remake of High and Low that he and Martin Scorsese considered making. Finding the ending lacked something, Mamet describes his solution: have Gondo/King’s son tell him not to spend the ransom for the chauffeur’s son. Realizing that his child has become a spoiled and entitled jerk, King insists the son help him rescue the friend.

Would I watch that version? Sure. But it would take the film out of the procedural realm, and the procedure is what makes High and Low special. That and the moral decision that falls to King.

(Not that I know better than any of them, but I’d just take out the accomplices. Once the cops find the kidnapper, the story’s over. Just my two cents.)

It’s fitting that so much of Kurosawa’s cast is carried over from Seven Samurai, because High and Low and a similar dynamic—a group of capable men (Gondo and the cops) caught between human predators and prey (the chauffeur’s body language is the same as the peasants in Seven Samurai, looking almost ashamed to draw breath).

This doesn’t do justice to the film’s blocking, cinematography, editing, pacing, and the incredible detail Kurosawa brings to the adaptation. But it’s also worth mentioning that a great deal of this is directly from McBain’s book.

When the Spike Lee remake Highest 2 Lowest comes out, I’ll revisit this.

Such an interesting read. I recently discovered “Stray Dog” and will add "High and Low" to my watch list.